BANK TREASURERS ROLL OUT THE BARREL

Bank treasurers expect to see their supervisors ease up next year after cracking down hard on the industry in the wake of the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank (SBNY), and First Republic (FRC) last year. They also believe regulators will be less biased against bank mergers and acquisitions (M&A). According to the FDIC, community banks with total assets below $10 billion shrank by 260 over the last three years, with just over 3,800 institutions at the end of Q3 2024. After the Crapo Act became law in 2018, which its sponsors billed as intended to help community banks, there were 4,600 community banks in operation. The industry is shrinking because de novo bank openings have been a rarity since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), as the ratio of de novo bank openings to bank mergers averaged 3% over 14 years. But even if regulators ease up on bank M&A, many transactions will be complicated to execute given the sizeable negative mark on seller fixed rate assets due to the concentrated series of Fed rate hikes between 2022 and 2023 and the persistence of high rates on the long end of the yield curve even after 100 basis points of rate cuts since last September. For example, between FY 2019 and FY 2021, an average of 166 banks merged per year. Since FY 2022, there have been only 96 bank mergers.

Beyond regulations, low interest rates and flatter yield curves have hurt the profitability of community banks. Over 14 years since the GFC, the effective Fed funds rate averaged 125 basis points, notwithstanding the last three years during which the rate averaged 400 basis points. The ideal banking environment also includes a positive-sloping yield curve. Still, since the GFC, the average spread between the 3-month T-Bill and the 10-year Treasury has averaged 125 basis points, whereas before, the average spread was 175. These days, the positive spread between the 3-month and the 10-year is less than 25 basis points. Bank treasurers generally still believe that the yield curve will steepen by more than 100 basis points over the next year, assuming the front end of the curve will fall, and the back end remains unchanged. Still, since the Fed began cutting rates, the back end is up almost as much as the front end has fallen.

Even before election night, they already knew that regulators would revise the Basel 3 Endgame proposal, so the only uncertainty remaining now after the election is the timetable for publication of a new draft, which may get pushed back well into next year. Regardless, they expect the final draft to be broadly in line with the original draft. Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) will be incorporated into regulatory capital calculations for all banks with total assets over $100 billion, and there will be a long-term debt requirement for large banks, though probably not as high as 6% of risk-weighted assets. Even if no new proposal was on the table, bank treasurers plan to manage their balance sheets holding higher levels of capital and liquidity than they held through past cycles, given the significantly higher market volatility and economic uncertainty in the banking landscape.

Bank treasurers would like to see better coordination between the different regulatory agencies. Matters of guidance and scope are a case in point. For example, the Fed, FDIC, and OCC each published separate guidance on custodial deposits and board governance, and both the scope and the text of these publications are different and very confusing for institutions trying to comply. Treasurers at small banks would like Congress to raise the limit on deposit insurance because they believe they are disadvantaged against their larger peers competing for deposits against banks perceived as too big to fail. They also want relief from the myriad reporting requirements, which taxes their limited staff resources.

Ignoring signs that inflationary pressures remain, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted as the market expected and cut the range for the Fed funds rate by 25 basis points to 4.25%-4.50%. It also lowered the spread of the rate paid on its Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) by five basis points. This cut may encourage cash providers to shift away from the Fed facility and back into the repo market. It will also help take the pressure off primary dealers looking for financing as they manage the Treasury’s growing debt issuance. Nevertheless, reserve deposits remained abundant, at $3.4 trillion.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter-December 2024

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Congress had only good intentions when it passed the Volstead Act in 1919 to ban liquor sales in the U.S. over Woodrow Wilson’s veto. Demon rum was a national scourge, destroying lives and livelihoods. Hospital wards overflowing with the sick and dying as a national epidemic of liver cirrhosis swept the nation. Economists lamented lost worker productivity and absenteeism rates while struggling families, victimized by violence and abuse in their homes, watched helplessly as their dreams drowned along with their breadwinners in a bottle of rum.

Something had to get the nation’s workers out of the saloons and beer halls and back onto the assembly lines and factory floors to ensure they would show up on time, all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, and ready to boost U.S. productivity stats. So, why not ban it? Never mind that changing social mores around alcoholism might discourage drinking far more effectively than any law. Cut off its availability was the prevailing wisdom, and then maybe the nation’s intoxicated workers might reclaim their sobriety, might stop showing up late or missing work at the salt mines and sweatshops across America because they had one too many the night before. After the states ratified the 18th Amendment, which empowered Congress to do something about the problem, Congress banned it. America went dry, as did a hefty portion of the sin tax revenues the states and the Federal government had been collecting.

Initially, the law did what it was supposed to do. People did drink less, and alcohol consumption fell to 30% of its pre-prohibition level. Cases of liver cirrhosis fell dramatically. But as the saying goes, so to speak, where there is a will, there is a speakeasy. Just as the roaring 20s were kicking into high gear and Charleston was becoming a dance craze, the country returned to its sinful ways in no time. Crime surged, and homemade moonshine and bathtub gin flowed everywhere. Prohibition did not stop the consumption of alcohol. Aside from enriching the bootleggers, it just made it more expensive and a bother to obtain for the general public.

The government sent in its enforcement arm to bring the public in line. J. Edgar Hoover, Elliot Ness, and the Prohibition agents battled the Capones, Lanskys, and Lucianos, broke up backyard stills, smashed barrels, and sent rivers of beer running down America’s main streets. Not since the Whiskey Rebellion during the Washington administration did the federal government bring out the big guns against John Barley Corn like it did in the 1920s.

However, none of that mattered because, as far as meeting its stated objective, Prohibition was a miserable failure. Legislating against sin is a waste of time, and if people are determined to waste away their lives, risk their jobs, and neglect their families just to drink alcohol, nothing will stop them. Just throwing laws and law enforcement against them to prevent them from doing what they want is a waste of money and resources.

As the journalist H.L. Mencken wrote in 1925,

“Five years of Prohibition have had, at least, this one benign effect: they have completely disposed of all the favorite arguments of the Prohibitionists. None of the great boons and usufructs that were to follow the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment has come to pass. There is not less drunkenness in the Republic, but more. There is not less crime, but more. There is not less insanity, but more. The cost of government is not smaller, but vastly greater. Respect for law has not increased but diminished.”

Ineffective, heavy-handed legislation not only left the problem of alcoholism unsolved and wasted money and resources, but it also turned the public against the government. Repeal happened 91 years ago this month because the voting public concluded that the only thing it was doing was criminalizing the behavior of otherwise law-abiding citizens who drank responsibly, showed up on time to work the next day, and knew enough not to get into their cars after knocking back a few too many and drive drunk. They did not need laws to tell them to drink responsibly and find a designated driver. The end of Prohibition came because even women, alcoholism primary victims who filled the ranks of the Temperance movement that initially led to Prohibition, were wholeheartedly behind Repeal when it came.

Repeal Day was December 5, 1933. There was joy in America on that day. Happy days were here again, the skies above were clear again, and it was time to sing a song of cheer again. The public spontaneously rolled out the barrel and had a barrel of fun, drinking beer right in the middle of Main Street, oblivious of binge drinking’s hepatic health risks.

Free, free at last, at least from Federal laws. Because legislating booze was going to be the state’s responsibility after Repeal, and the very next day, all 48 states and territories got busy setting up licensing requirements, defining the minimum drinking age at 21, legislating against public intoxication, and writing open carry laws and blue laws. Because the truth is, there is always going to be regulation. Some states, including Mississippi and Oklahoma, remained dry for 30-40 years after Repeal. Regardless of who was regulating the sale and consumption of alcohol, federal and state tax collectors were back on the payroll the day after Repeal Day, as they fanned out in force to collect their dues.

Doors Close, Doors Open

As bank treasurers know, earlier that year in June, while Congress was mustering up the votes to end Prohibition, it enacted two other essential pieces of legislation designed to reform the banking system, the Glass-Steagall Act and the FDIC Act. In contrast to that whole theme with Repeal about getting government out of the way of the will of the people, the objective with these two laws was to rein in a broken financial system and get the government very much into its business and all up in its grill. Because the system had repeatedly proven that it could not police itself, and it was time, given the economy’s dependence on an efficient, safe, and sound financial system, it got the bank supervision it needed and deserved.

As the character Mrs. Reed says on the new Netflix show, “Black Doves,” one door closes and another opens. Having given up on fighting the liquor industry, Congress went after the banks. Congress and the new administration would hammer down hard on a sector that was the ultimate villain to everyday Americans. Maybe no one wants their corner bar or liquor store shut down, but if Congress wanted to make life miserable for bankers, “go have at it” as far as the public was concerned.

No one loved the banks, though they might know their local branch manager from their Rotary Club meeting. They especially did not love the big banks or had any love for the Simon Legrees and Silas Barnabys of this world, who repossessed the homes of the Great Depression’s unemployed and those devastated by the dust bowl, who heartlessly turned out Old Mother Hubbard and her family from their shoe. They denied critical loans to struggling businesses and lost the public’s hard-earned savings left with them for safekeeping. No one would shed a tear over some stepped-up enforcement measures against them.

The Great Depression and 9,000 bank failures later, Ferdinand Pecora pointed a fickle finger at the big banks and Wall Street for causing the disaster, and with that said, Senator Carter Glass and Congressman Henry Steagall sponsored a bill to prevent the causes of the last financial crisis with the hope of avoiding the next one. If they could have just banned the big banks, they would have, but the reality was that they were central to the capital markets and the payment system as it existed 91 years ago and as it still exists today. Had they banned big banks and forced them to break up, policymakers worried that the entire financial ecosystem would cease functioning.

But even so, Congress wanted the regulatory agencies to go down hard on the banks. Even if enforcement did not do that good a job policing Prohibition, they empowered regulators to get tough on the banks, who empowered examiners to force them to adopt safe and sound practices.

Glass-Steagall Regulated Competition Away

Which meant what exactly? Well, it's hard to say what that means today, but in 1933, it meant a lot of government control. Glass and Steagall demanded that investment and commercial banks no longer operate under one roof. Morgan had to be J.P. Morgan NA or Morgan Stanley, not both. And there would be no more lending money to officers of the bank. And inter-affiliate transactions would be limited, too. Talk about self-dealing and arms-length transactions! That was out. Also, paying competitive rates on deposits was terrible because competition between banks was bad and always caused them to do risky things. So, down with competition.

Glass-Steagall had good ideas about how to prevent disruptions of the financial systems and was well-intended. People today need to remember that while people on Repeal Day were going out and celebrating, many of them were still dealing with the trauma of losing their life's savings in a bank failure. The public demanded protection from the reckless banks that wrecked their lives. And if Congress was not going to be in the business of curing alcoholism anymore, at least it could do something about those big, bad banks. Banks were risky but necessary, so the public needed a law that outlawed risk or kept it to a minimum when banks were involved. With these noble intentions in mind, the Glass-Steagall Act preamble reads as follows:

“To provide for the safer and more effective use of assets of banks, to prevent inter-bank control, to prevent the undue diversion of funds into speculative operations, and for other purposes.”

Those other purposes were, first and foremost, to reduce the risk of bank failures. And to do that, the bill would increase the Fed’s regulatory oversight to include bank holding companies. It would also minimize conflicts of interest between commercial lending and securities underwriting and promote public confidence in the financial system. All of which are seemingly uncontroversial objectives. Carter Glass introduced the law that bore his name in 1932, but his bill was still in debate when the House adjourned that year because of one other sticking point: deposit insurance.

The big banks were against deposit insurance. What about the moral hazard they protested, knowing full well that they would end up subsidizing insurance for the small banks, which was and has been the case whenever the insurance fund needs a top-off or replenishment after paying for a wave of bank failures? Deposit insurance was what the small rural banks wanted if they would attract funding to make loans to small businesses about which big banks could care less. Small banks have always loved the idea of deposit insurance, which levels the playing field with their larger peers when they compete to raise deposits in the market because the big banks, unlike the small banks, are too big to fail. Congress could not even do away with them if they wanted, campaign donations aside.

Even today, the big banks continue to prove themselves as indispensable. For example, Congress established the FHLB system in 1932 to help small banks make mortgages. Large banks did not make those loans back then. However, the large banks today own much of the FHLBs issued debt and support the capital markets that bring that debt to market, so their eligibility to borrow from the FHLBs will not change, regardless of what Congress and the public intended or want today.

Initially, Senator Glass wanted deposit insurance included in the Glass-Steagall bill, but ultimately, it ended up in a separate law that gave birth to the FDIC. Like the bill that bore its name, the FDIC would be a separate full faith and credit guaranteed Agency of the Federal Government, like the Federal Reserve, a .gov. It would run an insurance fund from insurance premiums paid by the banks, but if losses ever exceeded the fund’s balance, taxpayers would be on the hook the payments to insured depositors. The original cap on insurance would be $5,000.

Glass-Steagall Worked Until It Didn’t

Unlike the Volstead Act, the Glass-Steagall Act aged well and stood the test of time. Bank failures were limited. In the ‘50s, for example, there were a total of 23 banks that failed, and there were 40 more in the ‘60s. Banking was boring. But in the ‘70s and ‘80s, around the time when the incidence rate for fatal cirrhosis of the liver surpassed its previous pre-prohibition high, bank failures began to take off for the first time since the passage of Glass-Steagall.

Eventually, everything gets outdated, even a law that kept the financial system safe and sound for decades after its enactment. Glass-Steagall’s Repeal Day came in stages. It all began in the 1970s when the Fed raised the overnight rate into the stratosphere, at over 20%, way above the Reg Q limit on what banks could pay on an interest-bearing deposit. But it also began because the money market fund industry was just taking off at the right time as a viable alternative for retail depositors looking for a competitive rate other than the one constrained by Reg Q. Thus, in 1980, responding to dire industry warnings that Reg Q was causing their disintermediation by the shadow banks and was hobbling the Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy, Congress passed the “Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act.” Congress wanted the law,

“To facilitate the implementation of monetary policy, to provide for the gradual elimination of all limitations on the rates of interest which are payable on deposits and accounts, and to authorize interest-bearing transaction accounts, and for other purposes.”

Here is an interesting factoid: Among the law’s other purposes was to let banks offer Negotiable Order Withdrawal (NOW) accounts as a workaround against the Glass-Steagall prohibition against paying interest on a checking account. But 30 years later, when the Dodd-Frank Act finally put a stake in Reg Q and repealed the entire regulation, banks were allowed to offer the public interest on checking. Consequently, banks no longer offer NOW accounts, although some are still on their books.

Easing, Tightening, and Repeat

Much more was changing in the 1980s, not just in the banking world. The country was in a deregulatory mood to overturn the Depression-era regulations intended to stifle competition. With a legislative and regulatory regime that businesses across America viewed as out of step with the faster pace of commerce, the public yearned to be free of government control. The public did not want the government to set its deposit rates but also wanted a higher cap on deposit insurance. So, in 1980, when Congress lifted Reg Q, the limit on deposit insurance was also lifted from $40,000 to $100,000. The banks and the public rejoiced until unforeseen consequences became the basis for the next bank crisis and the next tightening phase for regulations.

There are always two regulatory phases: a tightening phase and an easing phase. Tightening follows easing, and easing follows tightening. And it is a never-ending story. Making it more manageable in 1980 for banks to pay competitive deposit rates to reduce their disintermediation pressure because of Reg Q while raising the deposit insurance cap to $100,000 might have seemed a good idea to help the community banking industry compete against their larger peers. Still, it also led to the rise of the brokered deposit industry and a lot of fraud. It also caused a wave of bank failures over the next decade.

Over 1,600 banks failed in the 1980s, plus 3,274 savings and loans. Bank failures raged in the southwest, and according to the FDIC, from 1980 through 1989, 425 Texas commercial banks failed, including 9 of the state's 10 largest bank holding companies. Outraged, Congress responded to the Savings and Loan crisis by passing the "Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act" (FIRREA) in 1989, which included regulations for real estate appraisals used in federally related transactions. Four years later, as the industry was just beginning to recover from a decade of loan losses, including on commercial real estate, it also passed the FDIC Improvement Act (FDICIA) in 1993 to reform the FDIC and replenish the insurance fund. FDICIA also created Prompt Corrective Action, a rule that tiers commercial banks based on their regulatory capital ratios.

Easing begins right after tightening ends. Only a year after Congress passed FDICIA to tighten regulations on banks, it passed the Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994, which broke down whatever remaining barriers existed for a bank in one state to open branches in another. The rules in place since the Great Depression had to be eased because the financial system was changing, as depositors moved around from state to state and expected access to their checking accounts wherever they were at any time.

Glass-Steagall Repealed

Then came the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, also known as Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB), which repealed another central tenet of Glass-Steagall, the prohibition against banks and securities dealers operating under one roof. Like the Interstate Banking and Branch Efficiency Act, Gramm-Leach-Bliley only ratified what Congress believed the public wanted and what was already happening. And what was happening, other than Congress passing a law that let two Wall Street titans merge their respective institutions into what was supposed to be a financial supermarket but which in 25 years has never lived up to its promise or created shareholder value, was that existing banks were disappearing in waves of M&A at a faster rate than new banks opened to take their place.

From 1980 to 1999, over 6,000 banks, most small community banks, consolidated, leaving over 8,500 banks. The new law would speed up that trend by opening the door to more competition. Today, there are less than 4,000 banks, each with total assets under $10 billion and, in aggregate, total assets equal to $3.5 trillion. This number compares to the aggregate total assets of institutions with assets over $10 billion, equal to $20.5 billion. As its preamble stated, the bill would,

“…enhance competition in the financial services industry by providing a prudential, framework for the affiliation of banks, securities firms, insurance companies, and other financial service providers...”

The history of bank regulations in this country since Glass-Steagall is that bank failures follow every time Congress eases regulations. Less than a decade after it lifted Reg Q restrictions, the banking industry saw a surge in bank failures for the first time since it passed Glass-Steagall. After members of Congress congratulated themselves for bowing to the people's will and deregulating commercial banking when they passed Gramm-Leach-Bliley in 1999, bank failures surged again during the Global Financial Crisis less than a decade later.

Glass-Steagall Redux

Regulatory cycles repeat over and over. The following regulatory tightening phase culminating in the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, better known as the Dodd-Frank Act (DFA) of 2010, was designed to, as its preamble states,

“To promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end ‘‘too big to fail’’, to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes.”

The DFA did what it was supposed to; it promoted financial stability. And the Volcker Rule removed much of the restrictions in place with Glass-Steagall that Gramm-Leach-Bliley loosened. The lessons learned by Congress when it passed the DFA in 2010 was that the banking industry, especially the largest banks, needed more capital and liquidity to navigate financial markets in the 21st century. As Congress believed when it passed Glass-Steagall, enforcement (a.k.a., the Fed, FDIC, OCC, and the other regulators) would correct unsafe and unsound practices by banks and curb their reckless tendencies.

The financial system needed to find its way back to the Glass-Steagall era when bank failures were rare, even if major bank failures came back in style with Franklin National in 1974, a quarter-century before Congress passed Gramm-Leach-Bliley. As Congress learned in 1933, the largest banks may be the problem, but the financial system does not exist without them. DFA needed to ban and keep large banks at the same time.

Some bank treasurers might argue that the only thing it did for sure was reduce the number of small banks. There were just over 7,000 banks on the eve of the GFC and 6,500 by the time the DFA passed in 2010. However, most of the burden from DFA fell on the largest banks. Small banks were never going to do stress testing, they were never going to meet a Liquidity Coverage Ratio or Net Stable Funding Ratio test, and they were never going to include AOCI in their regulatory capital calculation. The only controversy with the DFA was the threshold for where big ended and small began.

Under DFA, the big banks would write living wills and simplify their corporate structures. This way, Congress' thinking went, they would be easier to resolve when they get into trouble. Theoretically, no bank would be too big to fail anymore. Above all else, everything needed to be transparent so the public would have faith again in the financial system's stability.

DFA would do what the public demanded it to do even though what it wanted conflicted with its other wants, even if it did and still does not know what it wants. Of course, it wanted a safe and sound system and did not want to encourage moral hazard by bailing out big banks. However, it did not want big banks to fail and take down the rest of the financial system. They wanted and still want tighter rein over bank risk-taking with safety and soundness in mind, but they also did and still do not want regulations that stifle industry competitiveness and profitability.

Calibrating Bank Regulation

Eight years after DFA, Congress did not repeal it, but it did calibrate it. Congress believed that the DFA went too far, its rules were too blunt, and it was hurting small banks. It believed these things about the DFA, even if only a few dozen banks were technically in scope for most of the DFA’s regulations, aside from consumer financial protection rules for mortgage lending and credit cards and a bunch of new reporting requirements that applied to maybe another 100 banks with total assets over $10 billion.

Enter the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act of 2018, better known as the Crapo Act, after its chief sponsor and head of the Banking Committee in the Senate that year, Mark Crapo. Under Crapo, DFA’s rules were calibrated for a bank’s systemic footprint, meaning the bigger the bank, the more rules it would need to follow. As its preamble stated, the law would,

“…promote economic growth, provide tailored regulatory relief, and enhance consumer protections...”

It will promote economic growth, as Senator Crapo explained at the time because it would help community banks by relieving them of costly rules, as he explained in a press release on October 2, 2018,

“This law’s primary purpose is to make targeted charges to simplify and improve the regulatory regime for community banks, credit unions, midsize banks and regional banks to promote economic growth.”

But instead, the community bank industry continued to shrink. In 2018, just over 4,700 FDIC-insured commercial banks were in operation, 1,800 fewer than in 2010, thanks mainly to consolidation. By the end of Q3 2024, there were less than 3,800 banks in the U.S. with total assets below $10 billion. Crapo may not have helped the community bank industry. Still, the credit union industry thrived under it, as its aggregate assets grew from $1.4 trillion at YE 2018 to $2.3 trillion by the end of Q3 2024.

Since then, credit unions have flexed their balance sheet muscles, acquiring over 60 community banks over the last five years. The numbers to date suggest there will be more than 19 credit union acquisitions of commercial banks in 2024, twice as many as the year before. Using their tax exemption as an advantage over commercial banks, they have been able to provide banking services to small businesses, with lower rates on loans and higher rates on savings and have been a significant factor in pushing community banks out of their traditional bread and butter loan and deposit markets.

Regulations Only Partly Explain Dearth of De Novo Bank Openings

There were 1,323 de novo bank openings over the first decade of the 21st century. There were only 86 more over the next 14 years. Bank industry lobbyists contend that the DFA put small banks out of business and buried under paperwork from the CFPB when funding costs were not crushing them. A 2024 community banker survey rated regulations as the industry’s number one concern, along with funding costs. In this year’s survey, 89% of community bankers listed regulations as their number one concern, up from 77% and 81% in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

Crapo may have breathed some life into the community banking industry since it passed in 2018, but unfortunately, it has not been enough to slow, much less reverse the declining trend in their ranks. Between 2010 and 2018, regulators approved 51 new commercial bank charters. In that same period, there were 2,020 bank mergers. Since 2018, with Crapo in place, regulators have approved 55 new bank charters, during which 767 banks merged (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mergers and De Novo Commercial Banks

Maybe more regulations need to be loosened, but after SVB’s failure in March 2023, Congress returned to wanting tighter, not easier, regulations. The public seized on Crapo’s calibration law for causing the crisis, even if there was no evidence that tighter regulations would have saved SVB, SBNY, or FRC. Regardless, politics always plays a role in the banking industry, and last year, politics demanded a response to the crisis, even though the rules were not the problem; mismanagement was. As former Fed Governor Randy Quarles wrote last year in the wake of the crisis,

“Several politicians have called for rolling back the carefully calibrated regulatory changes stemming from the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act of 2018—a banking-reform law enacted by strong bipartisan majorities…SVB’s failure wasn’t related to regulatory changes. Rather, it was a “textbook case of mismanagement,” as Michael Barr, the Federal Reserve’s Vice Chairman for Supervision, said Monday.”

While bank supervisors today have proposed tightening regulations in the wake of last year's regional bank crisis, for the record, Congress has never passed any new laws. The Basel 3 Endgame will be revised and re-proposed, although that timetable may extend with the change of administrations until all its appointments are complete. It is always possible that the Basel 3 Endgame never gets to the final draft stage.

If Crapo is still the law of the land and interest rates are still higher today after the Fed's 25 basis point cut this month than most of the last 14 years, why were there only two new bank charters through the first nine months of 2024 and just 6 in 2023? If it is not about interest rates and regulations, the yield curve might be holding back de novo banks. The curve is essentially flat from overnight to 30 years, but bank treasurers want a positive sloping yield curve, and flat is not enough.

The chairman and CEO of a large regional bank in the west believed that a yield curve with a lower front end and where the 10-year remains anchored would have the makings of an excellent banking environment for regional banks, telling analysts that,

“If we get to a more normal yield curve with…another cut or two, but with the 10-year remaining where it is today, that's going to be a healthy environment for regional banks.”

Rate cuts are not the key to better earnings. Regional banks need a normal yield curve to thrive, according to the treasurer of a large regional bank based in the southeast,

“Whether the Fed cuts 2 times, 3 times, 4 times next year is not really going to be a big driver…What's a bigger driver…is that you get some shape back to the curve...We've been in a meaningful inversion for quite a long time, which has been a headwind.”

Regional banks would love higher for longer, according to the chairman and CEO of a large regional bank based in the Midwest, provided it comes with a yield curve that is positively sloping,

“An upwardly sloping yield curve and…higher for longer…that's helpful.”

Because, given how deeply inverted the yield curve has been for more than two years, the steepening that already happened since the election was only enough to get the curve back to flat, which is hardly the positive sloping yield curve bank treasurers are hoping for next year. As the CFO at a regional bank in the southeast observed, the steepening trend is on pause,

“The steepening of the curve happened for a little while and then we got back to flat.”

Regulatory Relief: Promises, Promises

Bank treasurers are giddy about the incoming administration’s industry-friendly attitude to regulations and enforcement, expecting a significant pullback on some of the most onerous proposals bank supervisors have put forward since the regional crisis last year. Like the public celebrating Repeal Day 91 years ago, bankers are breathing a sigh of relief that the regulators will pull back their thumb on the industry and let it return to making returns for its shareholders.

If bank management had one wish for next year, it would probably be to get the regulators to finalize the new rules quickly. The president and CEO of one of the large GSIBs told analysts this month he just wanted to see the Basel 3 Endgame in print and on his desk as soon as yesterday, even though he readily acknowledged that this would require coordination so far lacking between the regulatory supervisors and, with the change in administration, not likely to happen anytime soon,

“We absolutely want it to be finalized. I mean it's just incredibly -- it's just a strange position to be in to have some of the most significant companies in this country unsure of what their capital requirements are going to be. I mean it's just -- it's a crazy way to run a system…It's the Federal Reserve, but it's the broader set of regulators and there are changes coming there.”

Regulatory Agencies Give Conflicting Guidance

Banks can have several regulators that supervise them depending on their size, including the Fed, OCC, and FDIC, and their dysfunction is evident in how they deliver guidance to the industry. For example, the FDIC proposed regulations in October 2023 requiring banks with total assets over $10 billion to beef up the board of director oversight over bank management. It would require boards of directors to take a more active role in decision-making than historically required by regulatory standards for corporate governance. Given that mismanagement was a key reason why SVB failed and that its board of directors failed to be sufficiently involved to check management’s reckless decision-making, the FDIC’s proposal sounds reasonable.

However, the FDIC’s guidance differs from the guidelines published by the Fed and the OCC, as analyzed by Davis Polk. For example, the Fed’s policies apply to banks with over $100 billion in assets. The OCC’s guidance applies to banks with over $50 billion in assets. And there are other differences. For example, the FDIC’s proposed guidelines would require boards of directors to comprise a majority of independent directors. The OCC’s guidelines require no more than two outside directors. The Fed specifies no number of outside directors.

Beyond these differences, the FDIC’s proposed guidance is more radical than that the Fed and the OCC published. Under the FDIC’s proposal,

“The board is responsible for establishing and approving the policies that govern and guide the operations of the FDIC Covered Institution in accordance with its risk profile and as required by law and regulation.”

The Fed’s guidance does not include guidance like this. The OCC Guidelines do not require the board or risk committee to review and approve any material policies around risk. Because doing so, the OCC believed, when it published its guidelines in 2014, would be burdensome,

“Board or risk committee approval of material policies…would be burdensome, and these policies should be approved by management instead.”

Unrealistic Unnecessary Rulemaking

Many regulations seem to address problems that only a few institutions face. The FDIC’s proposal on custodial deposits is a case in point. As written, the rules would heap reporting requirements on between 600 to 1,100 institutions, even though Vice Chair Hill of the FDIC noted that only a few dozen are the actual target of the regulations.

Since SVB’s failure demonstrated its lack of preparation to borrow from the discount window in an emergency, regulators have been pushing the industry to preposition collateral at the discount window to improve operational efficiency for using it as a funding source when they are not generally trying to discourage bank treasurers from viewing their FHLB as their de facto lender of last resort. The Senior Financial Officer survey found that bank management is very averse to going to the discount window, and even community banks feel the stigma issue. But prepositioning collateral with the Fed creates other problems for asset-liability and liquidity managers, which Governor Michelle Bowman flagged earlier this year as a reason for bank supervisors to take a step back from just writing new rules and consider the regulations already in place.

What Rules, Regulations, and Procedures Do Bank Treasurers Want Changed?

Bank treasurers would love to see less compliance red tape that has buried them and taxed their scarce resources. They are certainly not fond of Community Reinvestment Act reviews and answering inquiries from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. They wish there were rules that addressed real problems with solutions that do not create bigger problems. As the CFO of a large regional bank in the northeast said,

“We are in favor of smart regulations, what we've seen in the past several years is more and more regulations…I think…we need to focus on regulations that ensure risks are well contained and controlled, but also help the economy grow as well as make the bank stay safe and sound."

Unfortunately, if there is a Crapo 2.0 coming in the next year, it will not offer much hope for higher equity returns to shareholders. Whether the rules are tightening or easing, bank treasurers run their balance sheets as conservatively as necessary given the banking landscape. Given today’s craziness, whether they work for a big bank or a small bank, they will run their balance sheets with more capital and a larger liquidity buffer than they would have run it before. The reason is that it is prudent to do so. As the CFO of a large bank in the northeast told analysts this month,

“…we're going to do what we think is right at the end of the day, we have things that we do now that the regulations just don't make us do, like we're keeping all this money at the Fed. Right? We're doing it because we think it's the right thing to do because of our business. So, that's something that we don't have to do that, that we do.”

The chairman of the board and CEO of a large bank in the southeast agreed that no matter how much regulatory easing occurs, it will not have much of an impact on the way bank treasurers will run their bank,

“I don't think things change dramatically from a regulatory standpoint. We're building a great risk infrastructure that reflects the size and scope of our company…that will allow us to do all the things that we need to do to do for our business.”

Given all the market volatility that has gone on for the past 14 years since the DFA, given the heightened uncertainty, and given all the changes in the banking landscape, including an unprecedented run on large regional banks last year; the extraordinary actions taken by the Fed, from Zero Interest Rate Policy, to a 180 degree about face and massive rate hikes; from QE 1 and QE 2, to QT 1 and QT 2, to tapers and taper tantrums; to the establishment and use of the Standing Repo Facility, the Fed’s decision this month to lower the rate on the Reverse Repo Facility by 5 basis points to the lower bound of the Fed funds range, and the run-off of the Bank Term Funding Program; to debt ceiling showdowns, government shut downs, and 11th hour reprieves; to the lingering effect of massive government stimulus on economic numbers and the inability of the Fed to maintain a consistent rate and economic outlook from one meeting of the FOMC to another; for so many reasons, bank treasurers would foolish to run not their bank’s balance sheet with more capital and liquidity that they ran it in the past.

The world events give bank treasurers even more reasons to stock up now on capital and liquidity. As the chair and CEO of a large regional bank on the East Coast explained, if the incoming administration does what it says it is going to do, the most significant risk for the financial system might be where the back end of the yield curve suddenly spikes up,

“The fear factor on geopolitical stuff, cyber…those I'm always terrified of. We have concentrations in cloud providers and service providers that one outage…can take a lot of banks down at the same time. We're all concerned about that. Beyond that, the thing if I look at this economy and the behaviors and the expectations of the…administration, if they did what they say they're going to do, the thing that I would fear is kind of the Fed losing control of the back end of the yield curve. and just a real spike in back-end rates.”

The chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank in the Midwest explained that the changes promised by the incoming administration will turn an already complex economy into an even more unpredictable one,

“I think one of the challenges that we all face is there is no more complex ecosystem than the US economy and we're about to introduce a ton of change.”

So, as a practical matter, whoever is going to run the bank supervisory agencies at the Fed, FDIC, OCC, and NCUA next year, no matter what they decide to pull back on, the reality is that not much is going to change for what bank supervisors will expect, especially from the largest banks. As the chairman and CEO of one of those large banks remarked, come next year,

“…the actual supervision of a bank…I don't know that there's going to be much relief on that. Silicon Valley Bank did happen…Supervision at the margin may be a little easier, but I think people are a little bit too excited about that they're just going to let everybody run free here, with the change in regulation, I don't see that all.”

The cost of maintaining a higher stock of low-yielding liquid assets and higher capital levels is lower returns on shareholder returns than what they would have run with. The math is the math. Just in terms of the liquid assets carried on the balance sheet, as the treasurer of a large regional bank in the southeast told analysts,

“When we started talking about the range for the margin a couple of years ago…the liquidity regime has changed a bit. So, we used to maintain $2 billion to $3 billion of on-balance sheet liquidity in the form of cash. Today, that's probably $7 billion or $8 billion.”

If Nothing Else, Bank Treasurers Expect a Lighter Touch

Suppose regulators are not going to pull back that much on regulations. In that case, bank treasurers can at least celebrate this month that regulators will go easier on them than they have gone, especially since the regional bank failures last year. The chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank based in the southwest told analysts that based on his experience with the incoming administration from its first term in office,

“In terms of the new administration, from what we saw previously, there was a lighter touch from the regulators…We've been in an environment since the banking crisis in March and April of 2023 where regulatory oversight has been at a very high level across the industry. I do anticipate that will not go away, but maybe some of the requirements and some of the number of exams, et cetera, might be a lighter touch on a go-forward basis. We need regulations. We need oversight as an industry for all the reasons that we know. But I think what we saw previously was a little bit less onerous.”

The chairman and CEO of a large regional bank in the Midwest thought that bank stock prices were already reflecting that regulators were going to go easier on the banking industry than they have gone since the bank crisis last year,

“There's hope that the regulation will ease a bit. I think that's good for the economy and growth as well as for banks overall. I think you're seeing that reflected in bank stock prices.”

Regulators will not be so biased against large banks and will not try to block consolidation, the chairman and CEO of a large regional bank in the northeast predicted,

“We've had a lot of…bias against bigness, which I think will dissipate to a significant degree.”

M&A will pick up, which was probably the most significant change the chairman, president, and CEO of a large bank in the Midwest expected to see, but it will take time to materialize in transaction revenues,

“It has been a real challenge to get M&A deals approved…I find when there's a change in administration throughout my career, there's a long lead time before you really see changes. I think the biggest change, and it's not inconsequential, is just the approach to M&A deals getting through the system.”

At the same, regulatory light touch and less bias on bigness aside, he did not expect to see much consolidation in the banking industry because many bank targets carry bond portfolios with significant unrealized losses that will become realized on the day of the sale,

“I don't think that there is going to be consolidation in the industry. I don't see it…given…that unrealized losses become realized losses upon buying something.”

December 5, 1933, was a Tuesday, and it is safe to say that bank treasurers probably missed the festivities in the office because they faced a lot of work to adapt their bank’s balance sheet strategy to the latest legislative and regulatory realities created by the Glass-Steagall and FDIC acts. Probably a few of the dedicated souls even had to sleep in the office that night because they had so much work to do, which bank treasurers today can appreciate given their workloads. Besides, trained to think that the next piece of bad news is just around the corner, they probably were not in much of a festive mood anyway, aware that whatever rule gets eased today can easily be tightened tomorrow.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2024, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

The Treasury yield curve steepened this month, and for the first time in more than two years, the spread between the 3-month and 10-year Treasury was positive, if just barely at 20 basis points plus or minus as of mid-month. (Slide 1). The yield on the 10-year increased by nearly 100 basis points, to 4.5%, since the Fed began cutting the Fed funds rate last September, which powered the curve out of negative territory. Typically, when the yield curve was steepening before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the spread between the front end and the long end of the yield curve tended to peak at close to 400 basis points, but since then, the last time the yield curve went through a steepening phase, the peak spread in 2022 only got as wide as 200 basis points (Slide 2). Given that the Fed just signaled that it was too optimistic last September to cut rates four more times next year, the chances are that the current steepening phase will fall short of even the 2022 peak spread.

Over the past six months, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) has averaged a few basis points over the effective Fed funds rate (Slide 3). In contrast, it averaged a few basis points earlier this year through the unsecured overnight rate. The positive spread may reflect liquidity stress in the repo market because there may be insufficient cash providers to meet primary dealer demand for general collateral financing. The Fed reduced its Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) from $0.8 trillion last June to under $0.2 trillion this month, which should help ease some of the stress in dealer financing. The Federal Open Market Committee also adjusted the RRP rate to match the bottom of the target range for the Fed Funds rate. These actions should help improve the cash supply in the repo market. But reserve deposits remain very abundant at $3.4 trillion.

When assets on the Fed’s balance sheet, such as the System Open Market Account (SOMA), increase, reserves increase dollar for dollar. However, when a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet increases, reserves decrease dollar for dollar. Most liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet, such as the Treasury General Account and the RRP, can increase or decrease over time, decreasing or increasing reserves accordingly. However, Currency in Circulation can only increase; it never decreases. In September 2019, when the repo market suffered a severe financing shortage, and SOFR jumped by 300 points overnight, there was more currency in circulation than there were reserves on deposit at the Fed (Slide 4). The Fed’s paper money liability was growing at 4% a year at the time, contributing to the downward pressure on reserves because there was more paper money, at $1.8 trillion, than reserves, at $1.4 trillion. So, a 4% increase in currency would produce a 5% decrease in reserves. In the last five years, however, currency in circulation grew by only 1% a year, and equal to $2.4 trillion today, it is still $0.9 trillion smaller than the balance of reserves, at $3.4 trillion.

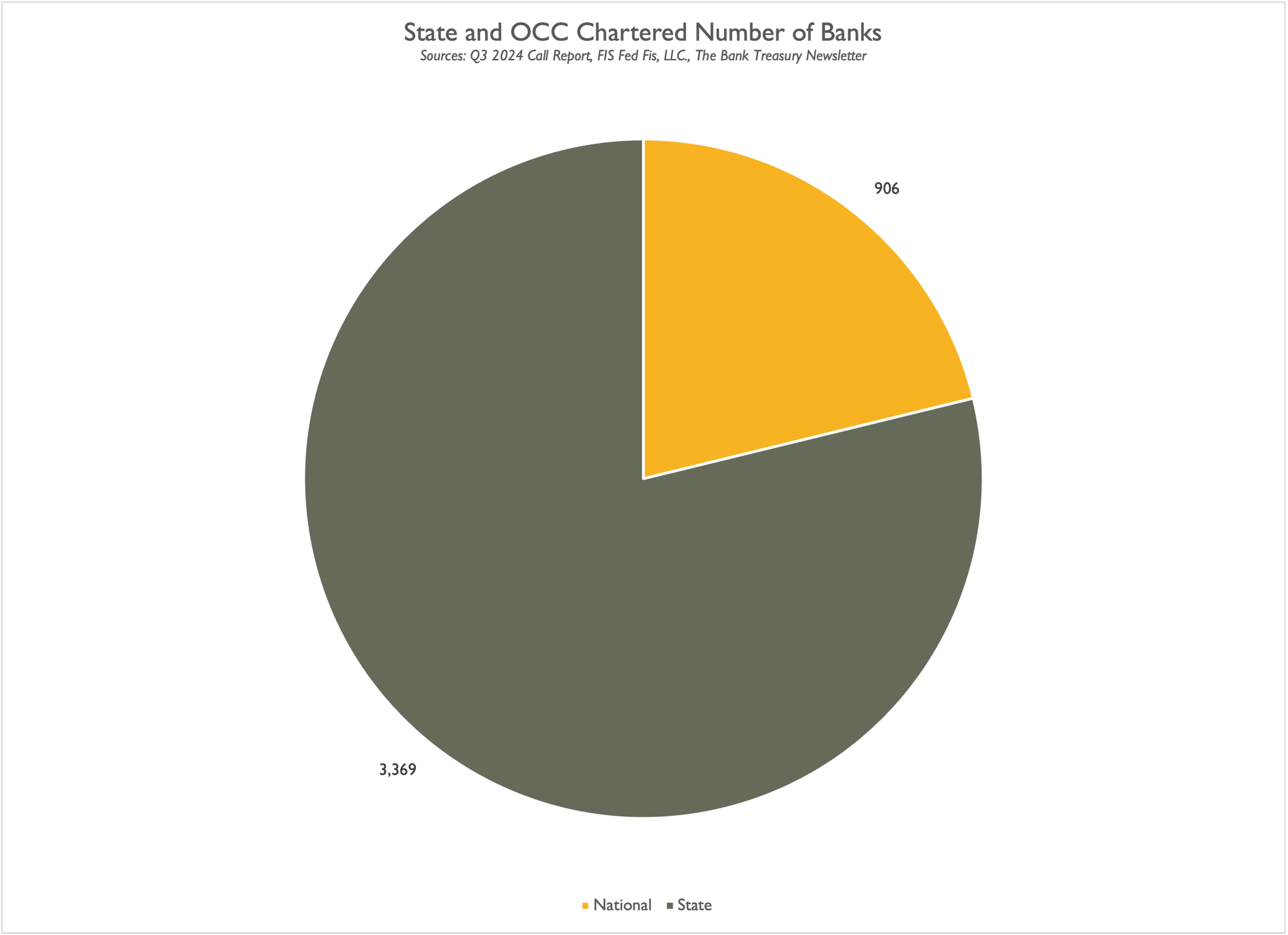

Bank treasurers reported that deposit outflows stabilized and are beginning to reverse, but the money market funds have been growing at their expense (Slide 5). These pressures encourage consolidation, especially among community banks with assets under $10 billion. Thus, FDIC-supervised banks fell from 4,700 in 2010 to 2,800 in 2024 (Slide 6). While the number of state-chartered banks in the U.S. might out-number the number of OCC-chartered banks by more than 3-to-1 (Slide 7), on September 30, 2024, the 906 Nationally-supervised bank total assets equaled $15 trillion, compared to the $7 trillion of total assets owned by state-chartered banks (Slide 8). Not only are banks buying other community banks, which drives the depletion of their ranks, but credit unions are also acquiring community banks as M&A transactions at a record pace (Slide 9).

Before the GFC, investors in de novo banks were opening more than 100 a year. Since the GFC, the average number of de novo bank openings has been five a year, with only two new banks through the first nine months of 2024. M&A transactions between banks fell off in 2023 and got worse this year, with just 55 transactions in 2024, compared to 100 in 2023 and 145 in 2022. The pace of M&A activity between banks would be faster, except that many prospective sellers are sitting with deeply underwater fixed-rate assets that a buyer would need to mark to market and realize the loss up front on the day of sale (Slide 10). Regardless, with 55 banks that merged and only two new banks that opened, the community banking industry looks set to continue to shrink its ranks next year.

Return to a Positive Slope

Historically Steepest Yield Curves

Repo Market Pressures Seem To Be Increasing

Abundant Reserves Exceed Paper Money

MMFs Grew At The Expense Of Bank Deposits

FDIC Supervising Shrinking Pool Of Banks

State-Chartered Banks Outnumber OCC Banks…

…But OCC Supervises Twice As Many Bank Assets

Credit Unions Buy Out More Banks

Investors Still Have Little Appetite For De Novo