BANK TREASURERS IN THE DESOLATE WILDERNESS

With the presidential election behind them, bank treasurers are hopeful for the coming year. They expect a significant rollback in proposed bank regulations and those already on the books. Heading the list of proposals is the so-called Basel 3 Endgame, which they believe will either be shelved entirely or significantly revised with less stringent requirements. Of all the regulatory capital proposals that emerged after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank last year, they expect that banks with $100 billion to $250 billion in total assets will include their accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) in their regulatory capital calculation. However, they also expect that if regulators pass this rule, they will be allowed a reasonable transition period to limit the impact of the change on regulatory capital.

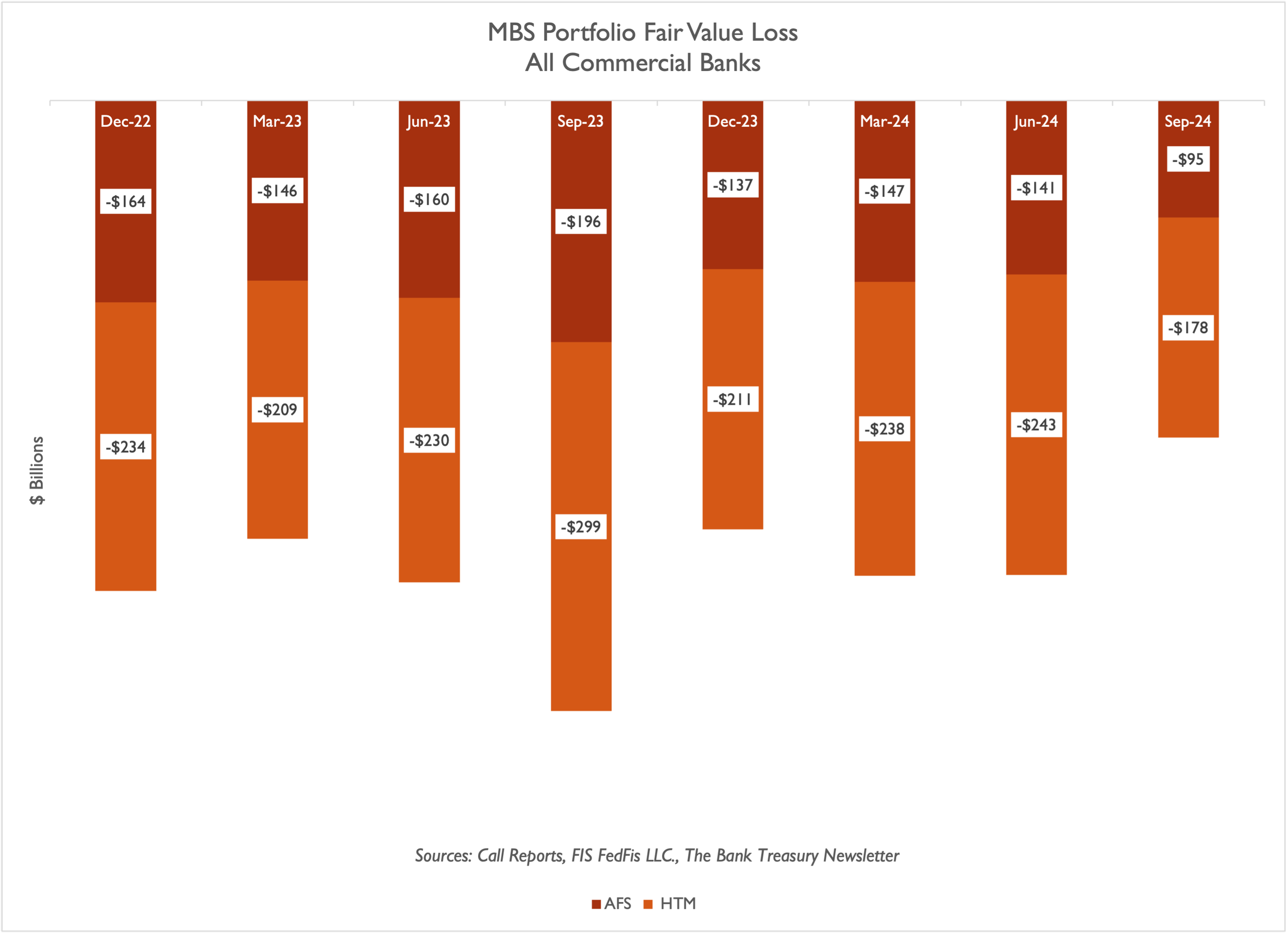

At the end of Q2 2024, the difference between the fair value and amortized cost for the available-for-sale (AFS) and held-to-maturity (HTM) securities for all commercial banks equaled $364 billion, or about 18% of tangible common equity (TCE). This loss improved over Q3 2024 to $273 billion, or about 13% of TCE, thanks partly to significant bond portfolio restructuring over the year. Most of the industry’s remaining underwater bonds include low-coupon mortgage-backed securities.

For bank treasurers at institutions with total assets exceeding $100 billion, regulatory relief in the new administration they believe will mean they would not need to meet a long-term debt requirement as part of the Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC) rule. They believe the rule would be costly, depress shareholder returns, and shift core banking businesses to non-bank competitors.

Other proposals on their list, which they expect or would like to see revised, include the FDIC’s proposed re-definition of brokered deposits in the wake of the Synapse bankruptcy last year, which had been a deposit broker with extensive business in the community bank space. The FDIC also proposed to require board members at institutions with total assets greater than $10 billion to take a more active managerial role, which bank treasurers believe would make it very difficult to recruit board members if adopted. Even without formal regulatory capital and liquidity management regulations, bank examiners at the Fed, Office of Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and FDIC are paying closer attention to the quality of bank management. They are less tolerant of lapses in governance, are challenging interest rate and liquidity risk assumptions, and demand that managers demonstrate their ability to adjust their course of action as scenarios change.

Bank treasurers are optimistic about the business climate, which will mean more lending and improved profitability for banks if it improves as they generally expect. In line with these expectations, they also expect, or maybe hope, that the yield curve will steepen, which currently is flat, plus or minus 10-20 basis points. While they believe that further rate cuts by the Fed would help spur lending and help increase the fair value of their underwater bond portfolios, their most important need to meet their net interest margin (NIM) and net interest income (NII) goals would be a positively sloped yield curve.

Along with the rest of the capital markets, bank treasurers are less confident about the path of interest rates over the next 1-2 years post the election than before. According to the CME’s FedWatch Monitor, the probability that the Fed will keep the Fed funds rate unchanged when it meets next month for the final meeting of the year of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is 50/50.

The primary asset-liability management to-dos for bank treasurers in Q4 2024 and next year include 1) shifting cash held overnight at the Fed to securities with durations under 4 years but still holding on to more cash at the Fed than they have historically held there, 2) shortening term deposit offerings to under six months to increase the balance sheet’s liability sensitivity, and 3) hedging both sides of their balance sheets to the degree economically possible. Bank treasurers, who are never good at predicting the future path of rates, are trying to keep their balance sheets rate neutral.

Bank deposits, as per H.8 data for all commercial banks, increased $0.2 trillion over the last year to $17.8 trillion, a 1% increase, which is well below the 6% average rate of deposit growth in the system since 1974. Bank treasurers blame the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) for the deposit growth rate but also believe the Fed is nearing the end of QT. Some believe that recent stresses in the repo market reflect a shortage of reserve deposits caused by a surge in new Treasury supply and a Basel 3 Endgame requirement that Global Systemic Important Banks (GSIBs) calculate their capital surcharge based on average instead of period-end balances. However, since the start of QT, the balance of reserves has stayed unchanged at over $3.1 trillion. The Treasury also has $800 billion in its Treasury General Account (TGA), which could boost reserves if Congress is unable to raise the debt ceiling when the suspension agreed to in June 2023 expires at the end of the year, which would force the Treasury to run down the TGA balance until it does.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter November 2024

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Bank treasurers have more in common with the Mayflower Pilgrims than they might first imagine. But before we explain why, as bank treasurers gather around the Thanksgiving table later this month, let’s tell a story.

A Little History

When they arrived, the place was, as Nathaniel Morton, William Bradford’s nephew and secretary, later wrote, a “hideous, desolate wilderness,” unsurprising considering that we are talking about Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in the late fall and early winter. They were cold all the time, their clothes never got dry, and just generally, forgive the blasphemy; Plymouth was a miserable hellhole for the damned. Of the 102 passengers who came over with Bradford on the Mayflower in the year of our Lord, 1620, half did not make it through the winter.

Massasoit, the head sachem over the Wampanoags, a people who had been living in the area for longer than 12,000 years according to archeologists, was waiting for them at Plymouth Rock when they arrived. He ordered his people to teach the Pilgrims how to grow corn, sweet potatoes, and pumpkins, hunt for turkeys and ducks, fish for cod, and go clamming for clams. (Lobster trapping and oyster harvesting were included in an advanced class to be determined.) Without his help, the colony would have starved if not frozen to death because the Pilgrims were clueless about basic wilderness survival skills.

Sure, if you need a hat, dress, suit, or someone to fix your watch, no problem. The Pilgrims had you covered. But farming, hunting, and fishing? No clue. They probably would never have imagined that a lobster could be angry or that it was possible to combine creamy and salty in a chewy texture called clam chowder. The Pilgrims were so thankful for his help that they invited him and his people to join them at the first Thanksgiving feast a year later.

That is the story bank treasurers remember when they played a dancing turkey in the school play. But no one tells you they stepped into a delicate situation when the Pilgrims signed the Wampanoag Treaty of 1621 with Massasoit. The question they might have been asking themselves as they sat across from their new friends and passed the stuffing and the gravy was why. Why was Massasoit helping them?

Forget brotherly love. That might have gone down in Philadelphia as an explanation, but this was Cape Cod. As far as the Wampanoags were concerned, the Pilgrims could go to H, E, double toothpicks.

The peace treaty was not exactly well received among his people, many of whom would have been just as happy to eat them for dinner if they had been cannibals, which archeologists believe they were not and could have stomached them if they were. Forget that the Pilgrims did not bathe, smelled terrible, and had bad teeth and breath. They and their lice-ridden, unwashed kind were probably responsible for bringing the plague to the region.

They had even more reason to wish them dead. Remember Squanto? He spoke English, worked with Massasoit, talked with the Pilgrims, and probably taught them the secret to making the perfect pumpkin pie. Periodically, European slave traders raided native villages and captured natives to work back home in Europe in the fields and salt mines. He was one of those captured natives, though he escaped and returned home. The Pilgrims were probably the last people he would have wanted to help.

Massasoit’s Problem

But you see, Massasoit had a problem with the Narragansett, a rival tribe in the region. Until just before the Pilgrims showed up, the Wampanoags and the Narragansetts were regional rivals. They had an understanding. Narragansetts did not mess with the Wampanoags, and in return, the Wampanoags respected the Narragansett hunting grounds and fishing holes.

But then the Wampanoags were hit with a plague, and the “Great Dying,” as they called it, devastated them. From a population that archeologists believe numbered 5,000 to 7,000, the Wampanoags fell by more than half. The Narragansetts, who somehow managed to escape whatever killed off the Wampanoags, got very rude and began bullying them and pushing them around, brazenly going for turkey shoots on their hunting grounds and dropping lines in their fishing holes. As frustrated as Democrats in Washington, D.C. will likely be next year out of power, there was nothing the Wampanoags could do about the unlevel playing field given their diminished numbers, which would take more than one election cycle, if not at least a generation, to fix.

They were in trouble. Helping the Pilgrims make it through that first winter might have been their death in the long run, but the Narragansetts were an immediate existential threat. Massasoit, who probably never heard of Faust, needed help quickly.

Enter the Pilgrims. The Pilgrims may have been good for nothing when it came to farming, hunting, and fishing, and the hats, dresses, suits, and knickknacks they brought with them to trade were pretty much worthless as far as the Wampanoags were concerned, given their propensity for beads and shells. But they had muskets, a game changer from Massasoit’s perspective. Muskets were worth a conversation. William Bradford and Edward Winslow looked back years later, writing that Massasoit,”

“…has a potent adversary in the Narragansetts, that are at war with him, against whom he thinks we may be of some strength to him, for our pieces are terrible to them.”

Massasoit wanted to restore the balance of power with the Narragansetts and keep the other tribes at bay, and the Pilgrims were just the people to help him do it. The Pilgrims would fight the Narragansett for the Wampanoags, and in return, the Wampanoags would teach the settlers how to get out of the corn maze in which they had gotten lost.

It would all be great until it was not, as with all unforeseen consequences and tricky situations. Helping the Pilgrims survive that first winter also helped more settlers come in the following years, which increased the colony’s population to the point where it threatened the Wampanoags even more than the Narragansett ever did. A half-century later, Massasoit’s son, Metacom, for who an avenue in Rhode Island was later named, got so mad at the Pilgrims one day that he led a massacre, killing over 1,000 settlers.

But what does all this have to do with the world of bank treasury? Our readers must ask themselves. History lessons are fine, but time is money.

Bank Treasurers and Pilgrims Are Nothing Alike

Maybe our readers should consider putting this month's newsletter edition aside now. What possible connection could there be between Pilgrims and bank treasurers? And they would not be alone in their skepticism. If we could interview a Pilgrim and ask if they felt any kinship with our readers, they would probably deny any existed.

Don't take this personally, dear subscriber; it is just that Pilgrims never dealt with asset-liability management issues, could not have defined the terms net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM), and did not even believe in paying, much less earning, interest on debt. Who knows how they would have felt about deposit lagging strategies for NIM or teaser loan rates to get customers to borrow? Charging interest was usury and banned in the Bible. Interest-earning and interest-bearing liabilities were just plain immoral.

And when they came to this country, they did not believe in private property. They were communists. Everyone worked together for the colony's good in that first year and did not own private property, which is also consistent with the fact that they were dirt poor. Later, it is true, they reorganized and became capitalists, and everyone worked their patch of land to produce what was needed to keep the colony going. But given their upbringing, they probably still had no love for banks or anyone working in the bank treasury department, for that matter.

Bank treasurers probably would not think they had much in common with the Pilgrims, leaving aside the fact that there were no banks in Cape Cod or anywhere else in New England when the Pilgrims came. And there were none for a long time until John Hancock, governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in 1792 chartered the Union Bank, a forerunner of one of the eight U.S. Global Systemic Important Banks (GSIB). What possible connection could there be between bank treasurers and the Pilgrims?

Considering their precarious circumstances, the Pilgrims must have worked hard and been under much stress. So, yes, bank treasury is also a lot of work and stress, and yes, bank treasurers may find themselves sitting in an interior office with no windows, with the air vent right over them where they sit, but calling their office working conditions a "hideous, desolate wilderness?" Really? That description seems a bit of a stretch.

It is not as if bank treasurers are in danger of literally dying from exposure to the office air conditioning during the summer. It is not as if they worry about starving to death if they do not run out and drop some seeds in the ground to grow a Caesar salad or hunt for a turkey breast on rye. They usually order take-out for lunch, anyway.

Guns Only Went Get You So Far

They also do not use muskets in their day-to-day. The gun arsenal the Pilgrims brought with them was a critical factor in their tribal relations, an ace in the hole of sorts if negotiations turned south if they played cards, which they probably did not, given that cards were sinful. William Bradford wrote about a violent encounter between the Pilgrims and a group of native tribesmen armed with their bows and arrows and how effective their guns were in crisis,

"The skirmish continued, with neither side gaining any advantage, until several of the Pilgrims, wearing coats of mail, rushed forth from the barricade and discharged their muskets together… and away they went, all of them.”

Guns certainly made an impression on the natives. However, guns could not secure long-term cooperation with the native tribes, which they needed if they were going to survive the winter. As they sought relations with the Wampanoags, Narragansett, and other native tribes in the region, they had to learn everything they could about the people, their languages, their needs, sensitivities, and beliefs, and how to exploit that information for the good of their fledgling colony. They needed intelligence, and you cannot learn intelligence about your neighbors behind the barrel of a musket.

Besides, the muskets were hardly a reliable solution to calming a hostile native population. Historians believe the Pilgrims had about 100 muskets. To say these guns would have been a pain to shoot would be an understatement, and it is doubtful the Pilgrims would have wanted to bet their lives on them surrounded as they were by thousands of hostile natives ready to use them for bow and arrow target practice if they wanted. The Pilgrims could not even shoot all 100 muskets simultaneously, given that there were 52 Pilgrims, including 25 children and four women.

No, muskets were not the most critical factor that saved the Pilgrims from getting killed by Squanto and a band of avenging Wampanoags, any more than they saved the colonists in 1622 in the Jamestown massacre in Virginia. The Pilgrims survived on their ability to maintain solid, working relations with the native tribes. Doing so meant more than meeting them once a year at Thanksgiving. It meant regularly going over, knowing everything about their families, sharing family photos, and passing around the peace pipe. Pilgrims made good diplomats, as are bank treasurers.

Pricing Only Goes So Far, Too

Bank treasurers do not use guns in their line of work, but loan and deposit pricing would be equivalent. Bank treasurers expect the people in their client-facing businesses to abide by their posted rates for loans and deposits. But pricing, like guns, only gets a bank treasurer so far. Because, as with all posted prices, just as with all rules and regulations, there will be exceptions.

Before they can make exceptions, bank treasurers need to know the customer. They need to “know” the loan and deposit officers who ask for those exceptions, too. They must regularly meet with and maintain a dialogue with all parties to the bank’s business on both sides of its balance sheet. Phone, Teams, Zoom, and face-to-face bank treasurers need to do it all because you can never know too much about the people you need to cooperate and collaborate with to generate stable NIMs and growing NIIs.

The CFO of a large regional bank on the East Coast explained to analysts this month that it is the bank treasurer’s job to maintain a regular dialogue with the bank’s loan and deposit officers. So much has changed in the markets, and as many banking organizations know these days, turnover is high, so bank treasurers always have new people to meet,

“The treasury department manages the interest rate sensitivity. The job of the businesses is to maximize revenue with our clients, and it is treasury’s role to neutralize the risk that we're taking. And those fundamentals need to continue to get reinforced throughout the company because there's always turnover and changeover. And it's been a certain amount of time since we've had a lot of rate changes that we're having now, both on the yield curve as well as the direction of the Fed and just making sure our business leaders know what to do and how to be successful moving forward is essential.”

And he underlined the point later in the Q&A, telling an analyst that,

“We need to focus on the fundamentals of banking…We must make sure people in the businesses price loans as well as deposits off our funding curve so that we make net profit on each of those transactions. “

Keeping NIM Stable When Rates Fall: Extend Earning Asset Duration, Shorten Deposit Duration, and Hedge

Their job is to get everyone at the bank on the same page, which is essential to navigating choppy waters. As the treasurer at a GSIB told analysts this month,

“My job here as treasurer is to help the company navigate through change, through choppy waters.”

How have bank treasurers kept their banks out of trouble? Keeping their interest-rate risk exposure neutral will keep their NII and NIM on track whether rates increase or decrease. The balance sheet was a little less asset-sensitive, the above-quoted GSIB treasurer explained, in part because he had been,

“…putting on a little bit more duration…Going longer in duration…protects NII volatility in a range of scenarios.”

The CFO at a large regional bank in the northeast told analysts his treasury team was trying to balance yield against stable earnings,

“…moving money from the Fed…into the investment portfolio…keeping our duration about 3.5 years. About half of what we are purchasing are positively convex securities. That means it's not going to get whipsawed with rates moving up and down…The other half we are putting into short tranche CMOs and more seasoned MBS. And the blend of those together, while we're giving up yield, will give us more certainty as rates change, our cash flows will remain much more constant than what maybe other portfolios might have from that.”

On the other side of the balance sheet, the CFO of a large regional bank in the Midwest told analysts his bank,

“…significantly shortened the duration of new time deposits. This time last year, the typical duration was 11 months, Now, it's more 5 months.”

Shortening term deposits helps create a tailwind when rates fall and is a resource for bank treasurers to turn to when they need ways to offset downward pressure on NIM when earning assets reprice at lower rates. Bank treasurers are always trying to keep their balance sheets balanced, so when rates are falling, they want to lean liability-sensitive, and when they are rising, they want to lean asset-sensitive.

The CFO of a regional bank based in the West told analysts,

“We try to take a very disciplined and systematic approach…to shift the exposure of the company to be as optimal as we possibly can. If you zoom back, we significantly increased asset sensitivity before the rate cycle began. I think in a very intentional way that served us very well to protect capital…Now we have begun to do the opposite and shift that exposure back toward more neutral.”

When they are not adding duration on the asset side and shortening duration on the liability side to try to keep things balanced, bank treasurers are putting hedges on both sides of their balance sheet. As the CFO from another large bank in the Midwest explained, he was using both receive and pay fixed swaps to protect the bank’s NII and NIM and keep them steady,

“We've been relatively neutral because we have virtually an equal number of receive-fixed swaps as pay-fixed swaps. The hedging is to help in the two different portfolios, meaning we have pay-fixed swaps that help protect our investment portfolio. So, when rates scoot up as they have, obviously in the last several weeks here, then we're protected. We're not exposed as much to that AOCI hit in capital. But if we just did that pay-fixed swap component and we did nothing else, then we would be heavy one sided on our interest rate risk profile, which we don't want to be. And so, on the other side of that, we have receive-fixed swaps…I look at the hedging to help put a bow around our interest rate risk profile or balance sheet management.

Bank Treasurers Gather Intelligence

Diplomacy is not just about maintaining cordial relations. Diplomacy is a form of intelligence gathering. When the Pilgrims were hanging out with Massasoit, they were not just formulating battle plans for him with the Narragansetts. They also learned critical information about the Wampanoags and the other native tribes. If the natives were getting restless, their deep connections with the Wampanoags that they developed could help save them one day from a surprise massacre. Intelligence gathering is an excellent way to avoid surprises.

Bank treasurers are all about avoiding surprises, so they spend a lot of time gathering intelligence as they make their way around the bank’s departments, talking to the loan officers, chatting over coffee with deposit officers and branch personnel, attending staff meetings and industry conferences, and even going to expensive client dinners and playing golf. They are always listening and learning. With the election behind them, they want to know everything they can about what their customers think, how they feel about markets, the economy, and their business opportunities for the coming year.

First Stop: The Treasury Department’s Front-Office

However, even before they leave their interior office to make the rounds around the bank, the first stop bank treasurers will make will be with their staff in the treasury department. They could probably spend all day there, considering the treasure trove of collective wisdom and insights they could gain from staffers sitting in the front, middle, and back offices.

The trading desk is in the front office, and because bank treasurers often start their careers on a treasury trading desk, it probably would be their first stop on their daily rounds. The trading desk is where they will get their market update. Sitting on the desk with them, traders would give them a rundown of the markets, what is rich and cheap, and what their capital market contacts say about the markets.

After visiting with the traders, bank treasurers move next to visit with the investment portfolio management team to review the portfolio’s average maturity and the average coupon coming on and running off. They might also want to know something about the cash flows from paydowns in the mortgage portfolio, given the latest backup in mortgage rates. The next stop is with the hedging team for a review of the latest opportunities left in the market to hedge the balance sheet and who might want to discuss the opportunities to use cost-efficient hedging tools, such as the Eris SOFR Swap Futures contract.

The front end of the yield curve moved quite a bit in the last month, as the inverted spread between 3-month and 5-year Treasurys narrowed to less than 20 basis points post-election from 60 basis points before the election and more than 160 basis points before the Fed’s 50 basis point cut last September 19th. When the yield curve was still inverted, bank treasurers were focused on ways to monetize it, adding forward starting swaps to protect against falling interest rates without paying the price in yield give-up they would have incurred to extend the duration in the portfolio in the cash market.

Regardless of the profitability of hedging at this point, as the CFO of a large bank in the Midwest explained, hedging is a cost that he would gladly pay to keep profits stable and consistent.

“ I don't look at it as it's helping or going to help us or hurt. It's to hedge and help us holistically manage the balance sheet.”

Before they leave the front office, bank treasurers will want to sit down with the officers on the funding desk. Funding officers have seen a lot more stress in their markets lately, particularly in the repo, where there was a spike in the SOFR rate over month end between last September and October.

Bank treasurers know that, despite suspicions by market participants that the Treasury’s debt financing supply and the Fed’s QT have squeezed liquidity in the repo market, the level of Federal Reserve deposits has not changed since QT began in June 2022. At $3.2 trillion, it is more than two times larger than the reserves in the system on September 15, 2019, when SOFR suddenly spiked up by 300 basis points to 5.25%.

Roberto Perli, manager of the Fed’s SOMA portfolio, told an audience this month that these stresses, though nothing like what the repo market saw in September 2019, bear watching,

“There is some evidence that intermediation frictions and tighter liquidity conditions are playing greater roles in repo market pricing of late, particularly around financial reporting and Treasury settlement dates. These frictions likely reflect a range of factors, including regulatory costs, counterparty credit limits, and other operational limits. These factors, combined with declining liquidity and increasing collateral supply, have likely contributed to the observed increase in repo rates around September quarter-end.”

But he did not believe the spike in the rate over month end was a sign that it was time to stop QT, as he continued,

“All this suggests that the recent widening of repo rates around quarter-ends should be carefully monitored, and my colleagues on the Desk and I are doing exactly that. But it does not on its own indicate that reserve supply is anything other than abundant…It also does not suggest that repo intermediation is becoming prohibitively costly, or that money market conditions are at risk of becoming disorderly in the near term.”

Repo is a critical assumption in a bank treasurer’s funding and liquidity management strategies. As the treasurer of a GSIB explained to analysts, he can only count his bonds carried in HTM as HQLA if he can monetize them, and the only way to monetize the bonds carried in HTM is through the repo market,

“HTM is about liquid asset monetization. Cash, treasuries…agencies and other highly liquid assets and our ability to turn that to cash when it's needed. And…since we're talking about HTM as opposed to AFS, the only viable path for that is repo…If there's an asset that we have, that seems like it's liquid, but for some reason, we can't operationalize the monetization…we just don't count it.”

The funding desk will also have comments for bank treasurers about the state of the bank’s contingency funding, how the proposal by the FHFA to ease restrictions on FHLBs to make overnight deposits at banks in interest-bearing deposit accounts could strengthen their liquidity strategy by expanding sources for contingent funding. Post the SVB failure and the criticism that the bank did not have operational and up-to-date connections to borrow from the Fed’s discount window and from the FHLB’s advance desk in an emergency, the desk would probably want to go over the availability of untapped lines, and the availability of deposit funding resources, such as offered by our corporate sponsors, R&T Deposit Solutions, and Stone Castle. Because, as the GSIB treasurer explained,

“For us, it's critical that we make sure everything works…We test on a quarterly basis, we'll test borrowing from the discount window…We move collateral in and out across different facilities, including the Federal Home Loan Banks. if you don't know how to get the collateral to the right place when it's needed, it's useless.”

Before bank treasurers get up to leave for the rest of their rounds, funding managers might also want to remind them that the Fed’s proposal to expand the hours for FedWire from 22 hours a day, 5 days a week excluding holidays, to 7 days a week, could have significant implications for the bank’s funding strategy over weekends if finalized as proposed. The proposal would ease congestion on FedWire around the weekend, which might have arisen since last May when markets moved to a one-day settlement for securities trading.

The Treasury Department’s Middle and Back Office

From the front office, bank treasurers will head over to the middle office, which in most bank treasury departments sits just a few feet away from the front office. The middle office is where the bank treasury strategy is formulated based on the data it collects throughout the business day. Staff there monitor changes in the balance sheet and analyze interest rate exposure. They design the bank’s funds transfer pricing model, are responsible for asset-liability management, and endlessly think about optimizing the regulatory capital used for the risk taken and returns earned. Bank treasurers go to the middle office for help to connect the dots between the transactions executed by the front office and, depending on the interest rate scenario, their effect on the bank’s financial performance.

For example, the constant refrain bank treasurers would hear on their rounds when they stop by their middle office is that rate cuts will be good for NIM and NII, provided the yield curve, which is essentially flat from overnight out to 30 years, finally steepens. A lot of bank treasurers believed just a few months ago that rate cuts would steepen the yield curve, and here we are 75 basis points of rate cuts later, and the spread between the overnight rate and the 5-year Treasury is still negative. However, lower rates would help with NIM and NII, according to a CFO from a Western-based bank,

“A gentle declining rate environment would work best.”

Lower rates would be great for NIM and NII, but banks also need a positively sloped yield curve. The CFO from a large bank in the Midwest pointed out that the spread between SOFR and 5-year Treasurys (Figure 1) was still inverted and a headwind against NIM expansion and NII growth,

“We benefit from rate cuts…but it's ultimately the shape of the curve…I always look at the SOFR versus the five-year Treasury. And right now, it’s still inverted…The Fed cuts and the curve stays at this level or goes higher…that's always going to be beneficial to us.”

Figure 1: 5-Year SOFR Spread

Maybe rate cuts are not even necessary to improve NIM and NII. Perhaps the only thing that would help banks here is a positively sloped yield curve, as the CFO from a regional bank in the Midwest told analysts,

“I think a higher rate environment where the short end stays a bit higher than was previously forecasted, let's say, a month ago, but the belly in the longer end is also higher is incrementally accretive to us or NIM overall…The way the world has evolved here in outlook at least is incrementally positive to us.”

Bank treasurers appreciate the models and forecasts prepared by the middle office, but experience has proved that projections and actual results always differ. Wrong is a word that comes to mind when bank treasurers think about their middle office. As the CFO of a regional bank in the southeast admitted,

“In the beginning of the year, we had four to six rate cuts in our outlook…we thought that we would have 3% to 5% loan growth, and we'd hit the peak on deposit cost. We were wrong on all three of those. The environment played out significantly different.”

Before leaving the treasury department, bank treasurers know it is always good to stop in on the back-office staff, which handles documentation, recordkeeping, reporting, and transaction validation. Much of what they do feeds into the reporting that the bank’s accounting department manages, and all bank treasurers know the details of how front-office transactions feed into the bank’s Generally Accepted Accounting Principal (GAAP) financial statements matter to the mission of bank treasury. You cannot manage through those choppy waters without good data.

However, the staff in the back office are working on some exciting ways to incorporate new AI technology into data management and improve efficiency within the treasury function. Bank treasurers can never be too current on the latest ways technology revolutionizes bank treasury management and risk analysis. Straterix, one of our corporate sponsors, for example, offers bank treasurers AI software that improves interest rate investment and asset liability management decision-making, analyzing tail risk events with greater precision than has been previously possible through conventional, static interest rate risk modeling.

Tribal Relations: The Other Bank Departments

After leaving the treasury department, bank treasurers head over to visit the other bank departments. They will see the loan officers who will tell them that lending is probably now, maybe on the verge of picking up, with the election behind us and rates going lower, assuming the scenario the FOMC laid out in the dot plot it released during its September meeting continues to play out as it projected, where the Fed cuts by over 200 basis points through 2027 to bring the effective Fed Funds rate back to neutral.

However, that projection has become more uncertain every day since the election. In fact, according to the CME FedWatch monitor, the probability of the Fed passing and leaving rates unchanged at the next FOMC meeting on December 18th more than doubled since November 5th to 50/50. But even so, bank treasurers would expect to hear an upbeat message from loans. As the CFO of a regional bank based in the West said, he hoped,

“Hopefully now with the election tucked behind us for the most part and more certainty that's come with that and perhaps even some confidence in the business community that, that can translate to a more constructive view of loan growth.”

The deposit officers also have good color for bank treasurers ready to tell them when they make their rounds. The CFO from a regional bank in the southeast told analysts that banks still have repricing beta going in the right direction, especially with commercial customers who might get a lower yield on their savings but can take consolation from savings on their borrowing costs. Offering some insights into the to and fro with their customers, she told analysts,

“I think deposit rates are going to keep going lower in the near term. Consumers were very, very sensitive to the fact that we were going into a rate cut environment. You couldn't turn on the news, we couldn't have a conversation with them. So, they were expecting that to get passed to them. We have a asset sensitive balance sheet, which means many of our customers already had their loan repriced. It's a little bit of an easier conversation when their loan goes down 50 basis points. That is usually much larger than their deposit, to say well, your loan went down 50 basis point, your deposits also going down 50 or 25 and net you're still winning on the deal, right? You're still saving more than you were making on your deposits.”

With the balance of SOMA at $6.1 trillion and running off at a rate of about $40 billion per month, bank treasurers generally believe that QT is nearing an end, even though Fed officials have yet to validate those views in their publicly released statements. Nevertheless, if QT is nearing an end, and the treasurer of a GSIB told analysts he believed it is, this would help deposits grow,

“We're near the end of QT…And so, therefore, I think the headwinds to deposit growth system-wide is probably mainly over…we think that going forward from here, we going to see a pickup in deposits.”

Tribal Relations: Bank Examiners

In addition to the Wampanoags and the Narragansetts, the Pilgrims met many other native tribes as they spread beyond the Plymouth settlement. The Mohegans were in northern Connecticut and the Berkshires, the Nipmuc were down by Rhode Island, and the Pequot were closer to Bridgeport, Connecticut. The Massachusetts hung out around Boston and Concord. The Abenaki were in Vermont and New Hampshire. As far as the Pilgrims were concerned, they tried to maintain good relations with them all, a refrain one always hears from bank treasurers and a rule they live by, especially when they meet with bank examiners.

Examiners are a little different from the other “tribes” that bank treasurers might meet with daily, so they keep a few things in mind when they meet with them, starting with the fact that examiners belong to multiple “tribes.” There are the Fed examiners, who come from one of the 12 separately managed Federal Reserve banks. Then there are the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) examiners, the FDIC examiners, and the state examiners. Bank examiners are a lot like the Abenakis, a native tribe pushing into Maine, which were fierce fighters and gave the Pilgrims a lot of trouble.

Bank examiners can be the same way. Just because, for example, the FDIC examiners asked for a report with X, Y, and Z information in it does not mean that the state bank examiners would just be satisfied with a copy of the report. Naturally, they would want their report to include other data. And, if your bank happened to have a bank holding company, the Fed examiners might want bank treasurers to prepare a special report just for them, too.

Bank treasurers know that they can never be too responsive to examiners when they come calling. They know that examiners are all about seeing the work that went into the finished report. They want to test assumptions and ask what-ifs. Never mind that this or that will never happen. Examiners want to hear from bank treasurers about what they would do if it did.

As bank treasurers all know from experience, the key is to keep calm and focus, above all, on maintaining good relations with all the regulators. While doing that, they can tell themselves that, just as the Pilgrims learned from the native tribes how to survive, bank examiners sometimes have good suggestions for living and surviving. As the chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank in the southeast said,

“We believe that having good regulatory relations and partnering with our regulators is important because a lot of the things that we've seen in our environment like stress testing, we find that to be beneficial.”

Tribal Relations: Shareholders and the Board

A group of investors, known as the Adventurers, financed the Pilgrim’s journey on the Mayflower. In return for their investment, which by today’s exchange rates equaled something like $500,000, the Adventurers expected that when the Mayflower returned to England the following year, its gunwales would overflow with beaver fur, timber, and fish. They were probably not very happy when it returned instead with just a few ears of corn, some pumpkins, and maybe a troupe of dancing turkeys left over from Thanksgiving.

Bank treasurers could probably sympathize with the Pilgrims who had tried to explain to the Adventurers that they had barely survived through the first winter and just to be patient because they would get it together and step up on shareholder returns. Bank treasurers, too, know what it is like to meet with the board to tell the members to be patient.

“Be patient,” they want to say because even though the bank’s bond portfolio is still far underwater and will drag on earnings over the next couple of years, the drag will diminish over time as MBS with 2% and 3% coupon rates eventually pay off and can be replaced with higher-yielding bonds. Yes, right now, if one compares the fair value of the investment portfolio for all commercial banks at the end of September 2024, both the AFS and HTM books, to amortized cost, unrealized losses total $273 billion. Thanks to some restructuring they did when the market rallied over the last year and pay downs, that loss is half what it was a year ago.

However, it is not just the business with the bonds or even the board’s disappointment with the low fixed-rate loans the bank has on its books that bothers them. That is bad, no doubt. On top of that, they cannot ignore the cost of all the extra cash bank treasurers are planning on carrying to protect against another Silicon Valley Bank-run scenario for shareholder returns. They do not want banks to fail, but they invested in beaver pelts at the end of the day!

Because the industry returns are just not that great, on average for all commercial banks, return on average equity in September 2024 equaled less than 10%. That is not a good return and does not create much shareholder value. And, yes, sure, the yield curve will steepen, maybe, and sure, borrowers will start borrowing, maybe, but until then, shareholders would not mind it if bank treasurers slimmed down on costs. Maybe charge the Wampanoags for attending the next Thanksgiving feast and see how that goes.

Maybe bank treasurers could start by cutting back on their department. Do they need all that staffing? Maybe get rid of the portfolio managers who bought the bonds that are dragging on returns. Even all that hedging that bank treasurers are busy doing. Sure, you want insurance, but not all insurance is cost-effective.

If nothing else, board members want bank treasurers to be held accountable. Not only because performance has been lackluster, to say the least, but also because the bank examiners, after they finish meeting with bank treasurers, meet with the board and ask them a ton of questions to see if they understand what bank treasurers are doing when they say they are managing assets and liabilities, interest rate risk, and liquidity risk.

A year ago, in October 2023, the FDIC proposed requiring board members at institutions with total assets over $10 billion to take a far more significant role in management oversight than they have previously done. As the proposal states, FDIC examiners will expect that directors will be,

“…responsible for selecting, monitoring, and evaluating competent management; establishing business strategies and policies; monitoring and assessing the progress of business operations; establishing and monitoring adherence to policies and procedures required by statute, regulation, and principles of safety and soundness; and for making business decisions on the basis of fully informed and meaningful deliberation.”

Even if the FDIC, soon to be without its Chairman, Martin Gruenberg, who announced his retirement this month, never turns its proposal into a final rule, bank treasurers know that bank examiners do not need a formal rule to push banks in the direction they want them to go. They call it guidance, which under his predecessor, Jelena McWilliams, meant it was not a rule, but who wants to pick a fight with a bank examiner?

Bank treasurers can expect more challenges with all the parties they deal with during the day. They will see more exception requests from their loan and deposit officers, hear more complaints from unhappy customers with their rate offers, get more projects from bank examiners, and confront a skeptical and restless board asking more questions. Their version of a “hideous desolate wilderness” is a bank treasury landscape colored by uncertainty and volatility. Like the Pilgrims, bank treasurers will need to stay close to all parties and keep on dancing.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2024, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

Bank numbers for Q3 2024 show that the unrealized mark-to-market loss on the industry’s mortgage-backed securities portfolio, counting bonds held in held-to-maturity (HTM) and in available-for-sale (AFS), improved $380 billion at mid-year 2024 to $273 billion at the end Q3 2024 (Slide 1). Some of the improvement reflects costly bond portfolio sales over the last year (Slide 2). Still, in the case of MBS booked in the HTM portfolio, where the fair value loss shrank from $243 billion to $178 billion, the improvement was due to paydowns on the portfolio. Nevertheless, the industry’s bond portfolio remains deeply mark-to-market impaired from the perspective of the last 20+ years (Slide 3), and the portfolio’s book yield (Slide 4), at under 3%, is still below a bank’s marginal funding cost.

On the other side of the balance sheet, deposit growth at 1% this year remains very slow by historical standards, looking back 50 years (Slide 5), over which time annual deposit growth averaged over 6%. Bank treasurers have compensated to a degree for the tighter deposit funding by tapping and holding onto wholesale funding, including brokered deposits (Slide 6) and Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances (Slide 7). However, deposit funding remains a profitable funding source for the industry given that demand deposits, though down from a peak of 27% of total deposits in September 2022, are still at 24%, well above the average since 2022 at 17% of total deposits (Slide 8).

However, bank profitability has been under pressure over the same time as net interest margin (NIM) consistently trended narrower over the last 20 years (Slide 9). No wonder the number of banks during this period fell and presumably will fall even faster after the new administration takes office next year (Slide 10).

Fair Value Losses Recede

Bond Restructuring Cumulative Cost=$27 Billion

Bond Portfolios Remain Deeply Impaired

MBS Book Yields Still Yield Less Than Fed Funds

Deposit Grow Well Below 50-Year Average

Brokered Deposit Mix Climbed To 14-Year High

Banks Hold On To Advances

Demand Deposit Funding Marginally Lower

NIM Trends Point Lower

Banking Consolidation Continues